Farhatullah Babar’s The Zardari Presidency memoir offers an in-depth look at Asif Zardari’s tenure as president of Pakistan during one of the country’s most politically tumultuous eras. This memoir fills a significant void in Pakistan’s historical narrative, as few political figures document their experiences, and fewer still attract widespread attention. Babar’s work, however, deserves recognition for its detailed insights into the intricate relationship between civilian leadership and military influence in Pakistan.

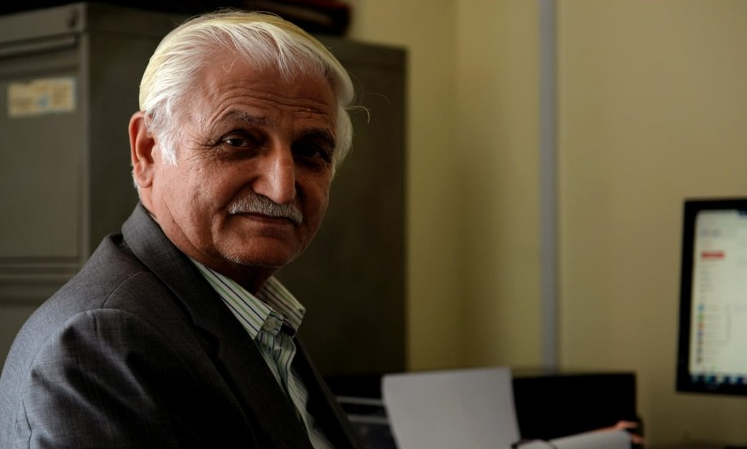

In Pakistan, it is uncommon for public figures to document their journeys, leaving a gap in the nation’s historical record. Politicians rarely pen memoirs, and even fewer receive significant attention. Farhatullah Babar’s book, The Zardari Presidency (2008-2013): Now It Must Be Told, quietly entered the market, overshadowed by the heightened tensions of India-Pakistan conflicts and an era of private rather than public political discourse.

This memoir does not chronicle Babar’s life but delves into his tenure as spokesperson for Asif Zardari during Zardari’s first presidency. The narrative provides a fly-on-the-wall perspective of critical political events, highlighting Pakistan’s enduring civil-military imbalance.

A Post-Benazir Political Landscape

The book begins after the tragic assassination of Benazir Bhutto, thrusting readers into the chaotic early days of the post-Musharraf era. The weak Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) coalition government operated under constant pressure, with civilians afforded limited political space. However, this is not a comprehensive account of those five years. Instead, Babar curates specific crises rooted in the deep-seated civil-military divide.

Key events such as General Musharraf’s impeachment, the 2009 long march, the Raymond Davis incident, and the Memogate scandal dominate the narrative. Foreign policy receives limited attention, and the book avoids exploring the PPP’s internal conflicts or broader governance issues in Sindh and other regions. Readers searching for a critique of Zardari’s leadership or an analysis of the party’s decline will find little satisfaction.

Highlighting the Core Crises

The book’s strength lies in its detailed recounting of significant moments. For example, the impeachment of General Musharraf and the lawyers’ march reveal the perpetual tension between democratic and military powers. Babar describes arriving at the presidency during the march, noting a heavy military presence—a stark reminder of the tenuous grasp civilians had on power.

Memogate, another pivotal episode, receives thorough treatment. The narrative captures Zardari’s breakdown and sudden flight to Dubai amidst escalating tensions with the military. Malik Riaz’s role as a messenger, warning the PPP that a departing helicopter carrying Husain Haqqani would be blocked, adds drama and depth to the account. The portrayal of these high-stakes moments reflects the fragile nature of Pakistan’s democracy.

Missed Opportunities in the Narrative

While the book succeeds in capturing major crises, it glosses over other significant events. For instance, the 18th Amendment, which redefined the federal structure of Pakistan, is barely mentioned. Similarly, the tumultuous relationship with the MQM and the revolt of Zulfikar Mirza receive scant attention. Even the imposition of governor’s rule in Punjab and Zardari’s hesitation to restore Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry are addressed superficially.

This selective storytelling might frustrate readers seeking a holistic view of the PPP’s tenure. Nevertheless, the detailed accounts of key crises compensate for these omissions, providing valuable insights into the challenges of navigating civilian governance in a militarized political environment.

Evolving Leadership and Decision-Making

A recurring theme in the book is Zardari’s transition from a consultative leader to a more insular decision-maker. In the early days, he engaged party colleagues in discussions, referencing Benazir Bhutto and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto to justify decisions. However, as his presidency progressed, he began making unilateral decisions, sidelining even his closest advisors, including his son.

This shift is evident in the book’s later chapters, where hurried writing and editing detract from the narrative. Repetition and disorganized content reflect the declining quality of Zardari’s leadership. Babar’s subtle critique highlights the consequences of this leadership style, emphasizing the challenges of balancing reconciliation and democracy.

Behind-the-Scenes Power Dynamics

Babar’s account shines in its depiction of the interplay between the PPP and the military. From the army chief’s offer to have Zardari checked at a military hospital during Memogate to the public antagonism between the two sides, the book illustrates the constant negotiation required to sustain civilian rule.

The narrative also touches on more recent developments, such as the thwarting of FATA reforms, the rise of the Balochistan Awami Party (BAP), and the election of Sadiq Sanjrani as Senate chairman. These episodes underscore the enduring influence of unelected institutions in Pakistan’s political landscape.

Gentle Critique and Subtle Lessons

Babar’s criticism of Zardari and the PPP is understated, reflecting the author’s journalistic background. For instance, he notes that Pakistani politicians, unlike Aung San Suu Kyi, fail to recognize that appeasement does not advance democracy. This critique, buried in the book, invites readers to reflect on the broader implications of Zardari’s leadership style.

The book also includes vignettes of political maneuvering and decision-making, such as Zardari’s support for Sanjrani’s Senate chairmanship. While Babar questions the backing provided to rivals like the PTI and BAP, he is less critical of Zardari’s motivations. This bias might limit the book’s appeal to readers seeking a balanced analysis.

Conclusion: A Memoir Worth Noticing

The Zardari Presidency (2008-2013): Now It Must Be Told is a compelling account of a turbulent period in Pakistan’s history. Farhatullah Babar’s insider perspective offers valuable insights into the challenges of civilian governance, the complexities of Pakistan’s civil-military relations, and the evolving leadership style of Asif Zardari.

While the book’s selective focus and uneven editing might disappoint some readers, its detailed accounts of key crises make it an essential read for anyone interested in understanding Pakistan’s political dynamics. In an era where political discussions are increasingly private, this memoir deserves a closer look.